Rethinking Assessment of Learning: Alternatives to Participation Grades

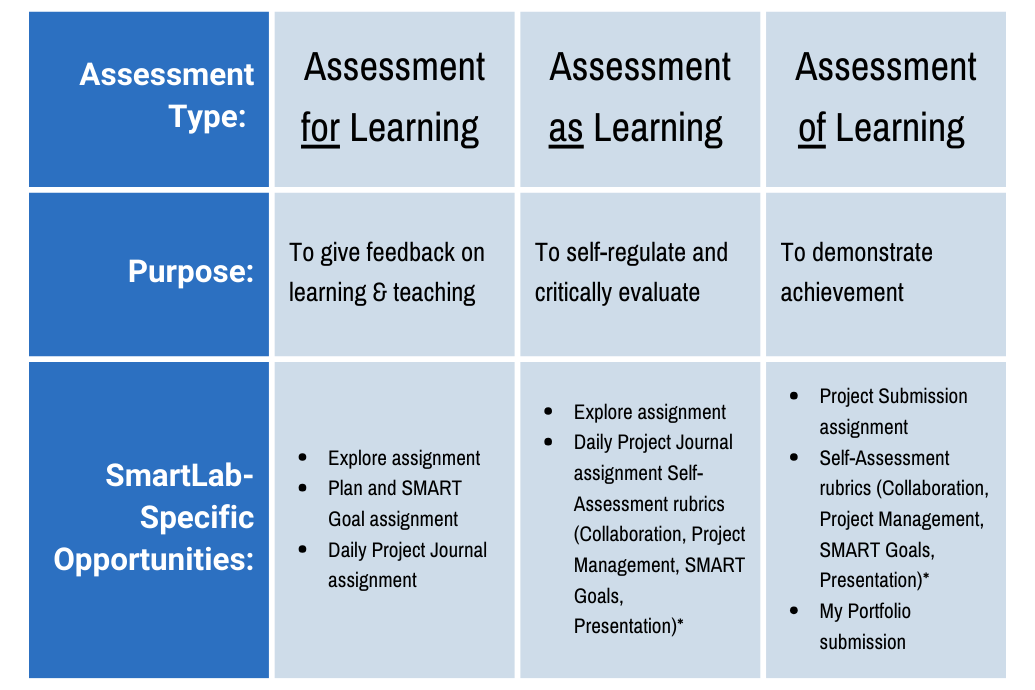

Over the last few months, we’ve focused heavily on assessment for learning and assessment as learning. If you missed them, you can read them on the SmartLab blog:

Assessment for Learning

- Formative Assessment in PBL: Checking for Understanding Throughout the SmartLab Learning Process

- How Do We Know What They Know? Empowering Learners with Documentation

Assessment as Learning

- Making Assessment Matter: Building Intrinsic Motivation with Learners

- Beyond Grades: The Importance of Self-Assessment in Project-Based Learning

While assessment for learning and assessment of learning can get mixed intermingled when it comes to grades, we’re going to focus on the primary purpose of summative assessment: to measure achievement.

In most educational spaces, grades are also used to communicate student achievement to stakeholders, particularly students’ families. In the SmartLab, “learning is different here,” so naturally facilitators grapple with how assessment and grading are different.

When time is limited and most learners are on different trajectories, working towards different goals, and using varied technology, how do you grade in a clear, fair, and realistic way?

For some, grading participation has been the solution to this grading challenge. Facilitators have highlighted a variety of benefits:

- Simplifies grading and saves time

- Applies to all projects and grade levels

- Creates low-stakes learning environment and safe space for risk-taking

- Encourages engagement

- Provides a grade boost

On the other hand, common participation practices can also introduce more subjectivity and opportunity for implicit bias. And, compared to other grades representing progress towards learning outcomes, grades based on participation overlook the significant learning taking place.

Throughout this article, we’ll address four questions about common grading practices and offer alternatives to consider implementing in your SmartLab:

- What do you grade?

- How do you award points?

- How do you address ongoing student growth?

- How do you communicate student achievement to students and families?

What do you Grade?

For grades to be accurate and provide useful information, it’s critical they are aligned to the targeted outcomes and learning activities (O’Connor & Wormeli, 2011). In fact, focusing assessment on learning gains can increase intrinsic motivation for students (Covington, 1992).

Alternatives to Participation Grading

One alternative, which aligns with the SmartLab philosophy, is to assess final project submissions and reflections based on the learning outcomes.

Learning Outcomes by Project Starter

- Grade project submissions based on the I CAN statements from each Activity Card (K-2) and project starter (3-12). You can use the Scope and Sequence to easily access the learning outcomes for all project starters your learners may be working on.

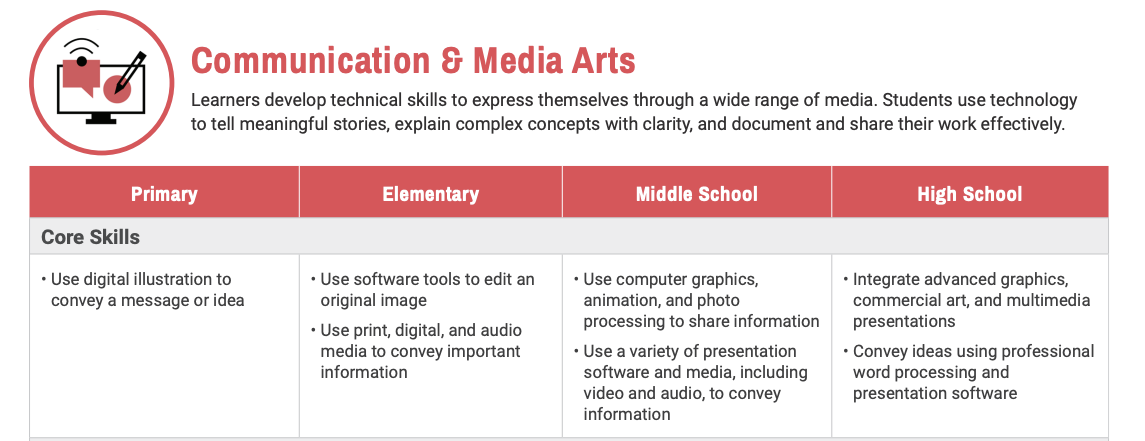

Learning Outcomes by Area of Exploration

- Grade project submissions based on the Areas of Exploration Core Skills. This focus reduces some of the assessment load on the facilitator and allows for repeated opportunities for learners to develop these skills. (More to come on the benefits of this approach!)

Another alternative is to focus on 21st Century Skills. For many, participation grades are intended to emphasize some of these skills, communication, collaboration, initiative (goal setting), but may not call them out specifically. This focus addresses the time and consistency constraints while valuing the transferrable skills that learners are gaining in the SmartLab. You can use the SmartLab self-assessment rubrics as a starting place for how to assess these skills.

Additional Considerations

Fair grading practices connect grades with outcomes that are 1) explicitly addressed through the curriculum or instruction, 2) within learners’ control, and 3) responsive to cultural beliefs and individual differences.

Consider:

- Attendance

- Completion of assignments

- Grammar and writing

- Participation in discussions*

*Participation in discussions is directly impacted by the format, the background knowledge required, and cultural differences present in the group. As you plan group discussions, consider:

- Does the structure give equal opportunity to all learners to participate?

- What background knowledge is required and what modifications can be made so all learners can engage in the discussion?

- What cultural differences exist among students and how does that impact eye contact, questioning, and discussion or debate with teachers and peers? How can the format be adjusted to create a safe space for all to participate?

Bottom Line: Grade skills and knowledge explicitly addressed through learning activities (project starters)

How Do You Award Points?

In the world of educational assessment, experts are clear on two points:

- Grades should be given on assessments taken AFTER learning has taken place (O’Connor & Wormeli, 2011; Feldman, 2020).

- Traditional grading using overall letter grades and 100-point scales are outdated (Feldman, 2020; O’Connor & Wormeli, 2011; Reeves, 2004).

Throughout the SmartLab Learning Process, and throughout the year, clearly distinguish between assessment for learning and opportunities for students to show what they know (assessment of learning) by only assigning grades to summative assessments.

Adapted from National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education

When you do award points, use a four-point scale, which provides more meaningful and equal increments for measuring learning. If you must use a 100-point scale, don’t give zeroes. Zeroes are hard to recover from and an unfair jump in points from a D to an F letter grade (Feldman, 2020; Reeves, 2004).

Four-point scales also lend themselves well to proficiency scales, which focus on the learning outcomes, provide useful information for ongoing instruction and intervention, and make grading very clear and easy. In addition, proficiency scales allow you to apply the same assessment tool to any related assessment. For example, consider a proficiency scale for goal setting. The scale could be applied to the learners’ goal setting skills, whether it’s for a robotics project, a circuitry project, or longer-term goal setting.

What Should You NOT Award (or Deduct) Points For?

If grades are designed to represent a learner’s achievement of learning outcomes, they should not be impacted by the timing of project submissions. If you’re struggling with getting learners to turn work in on time or turn it in at all, consider the root cause of the issue:

- Do learners have sufficient time to complete assignment submissions?

- Do learners understand the submission requirements?

- Are learners engaged and invested in the project?

- Do learners understand the purpose and value of documenting and sharing their learning?

- Are there outside factors impacting the learner’s engagement in the SmartLab?

Addressing these issues by giving a zero or deducting points is ineffective (Guskey & Bailey, 2001), and can be more effectively resolved through conversations with learners, as well as parents and administration.

Bottom Line: Use a four-point scale to assess summative assessments at the end of learning, i.e. project cycle.

How Do You Address Ongoing Student Growth?

Especially in the SmartLab, learners have repeated opportunities to develop core skills and knowledge related to the Areas of Exploration, which is accomplished through the spiraled approach in each grade band’s Scope and Sequence.

Assessment experts encourage teachers to allow students to continue working towards learning goals and resubmit work (Feldman, 2020; Marzano & Heflebower, 2011), which breaks through the ceiling that traditional grades place on students.

Though a learner may not have mastered parallel and series circuits during their first circuitry project with Squishy Circuits, maybe they developed a stronger understanding and application of those concepts later in the year when they completed a project with Snap Circuits.

The nature of summative assessment in project-based learning also means that sometimes learners may miss an element of their project submission. At first, this may look like a lack of understanding, but is actually a lack of evidence. In these cases, follow up with the learner to ask more questions or request a resubmission with more information.

As learners in the SmartLab revisit learning outcomes, allow that growth to be reflected by updating their grades.

Bottom Line: Allow learners to resubmit work, and adjust grades if learners later demonstrate mastery of learning outcomes.

How do you communicate student achievement to students and families?

Traditionally, a student’s achievement in a class is represented with an overall letter grade or score. If I think back to my high school report card, it was a single page that listed my classes with a letter grade and score next to each one. That was it. There was no information about the specific topics or skills I had successfully mastered or was struggling with.

This is the innate problem with letter grades: the meaning is unclear, they are commonly misaligned with learning outcomes, and grading can be inconsistent (Marzano & Heflebower, 2011).

If you can, implement standards-based grading by separating grades into the topics covered in the class and communicating achievement based on mastery of each topic or skill.

If you were previously assessing participation, specify the topics or skills that are ultimately learned and evaluated from that category:

- Communication

- Collaboration

- Project management

Even before grades are given, clearly communicate the topics addressed and corresponding success criteria to learners and families by sharing proficiency scales, a syllabus, or even a monthly SmartLab newsletter.

Bottom Line: Communicate success criteria clearly to stakeholders early on and use standards-based grading to provide useful information.

Reducing Implicit Bias and Grading More Fairly

First, you can use rubrics and proficiency scales to keep success criteria front-of-mind and ensure that grades are consistently aligned with evidence of learning.

Within the success criteria and expectations for grades, actively look for bias towards specific cultural values, personality traits, and behaviors. Ask yourself, “Are my expectations inclusive of all learners’ backgrounds and individual preferences?”

Additionally, it can be effective to grade learner’s work blindly. In LearningHub, group assignments are labeled with group numbers, which automatically creates some anonymity. After assigning an initial grade to student work, it can be beneficial to go back and identify the students who submitted it. Then, you can provide personalized feedback and document areas of growth.

Finally, share grading tools and assessment expectations with learners. Doing this increases student investment, agency, and equity (Feldman & Marshall, 2020). Not only can learners use this throughout the learning process to monitor their progress, but they can also advocate for themselves if a grade doesn’t accurately reflect their understanding.

In this article, we’ve highlighted many grading practices that can lead to more clear, useful, and fair grades for SmartLab Learners. Yet, implementing it all is a massive feat, and will vary based on each SmartLab’s goals, students, and constraints.

I invite you to take a moment to reflect on your grading practices, your unique context, and imagine what your ideal grading setup would look like. Next, apply the aggregation of marginal gains. What would a 1% improvement towards that ideal setup require? Start there, considering which strategies and practices from this article may aid in that gain. And when you’ve achieved that, consider the next 1%.

Over time, these marginal gains add up to significant change and progress toward your goals for grading in the SmartLab.

References

- Covington, M. (1992). Making the grade: A self-worth perspective on motivation and school reform. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Feldman, J. (2020). Taking the Stress Out of Grading. Educational Leadership, 78(1), 14-20.

- Feldman, J. & Marshall, T. R. (2020). Empowering Students by Demystifying Grading. The Empowered Student, 77(6), 49-53.

- Guskey, T. R. & Bailey, J. M. (2001). Developing Grading and Reporting Systems for Student Learning. Corwin Press.

- Marzano, R. J. & Heflebower, T. (2011). Grades That Show What Students Know. Educational Leadership, 69(3), 34-39.

- O’Connor, K. & Wormeli, R. (2011). Reporting Student Learning. Educational Leadership, 69(3), 40-44.

- Reeves, D. (2004). The Case Against the Zero. Phil Delta Kappan, 86(4), 324-325.

- Wiggins, G. (2006, April 3). Healthier Testing Made Easy: The Idea of Authentic Assessment. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/authentic-assessment-grant-wiggins